Magaxat | Survey (1976 - Present). Rudik Ovsepyan. August 26 - September 23, 2023. Historical Survey.

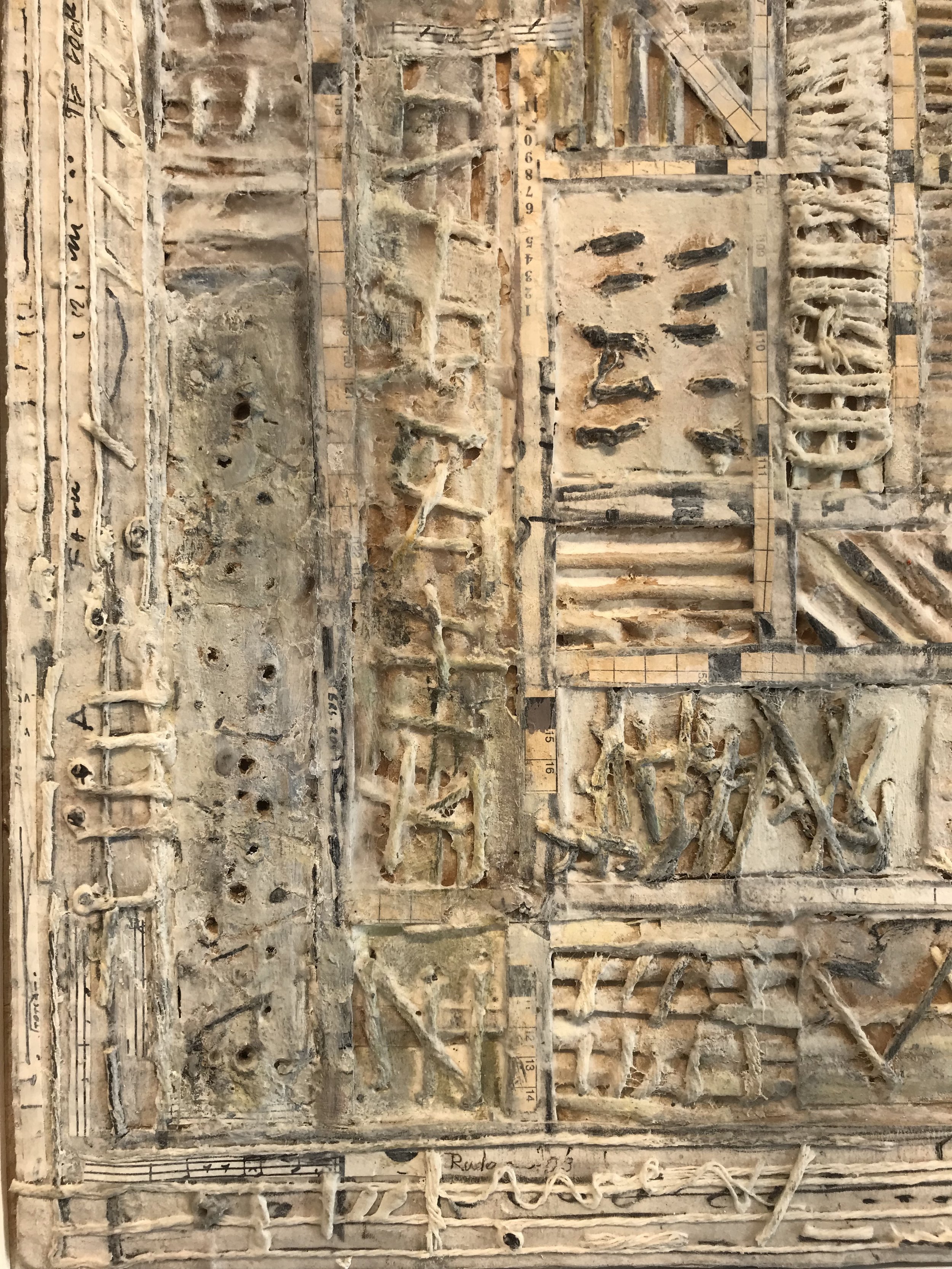

Untitled, 2005-2006. Magaxat Series. Mixed-Media on Cardboard. 17.5 x 17.5 inches.

Shut

Magaxat | Survey (1976 - Present)

Worker: Rudik Ovsepyan

Duration: August 26 - September 23, 2023.

Location: 2680 South La Cienega Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90034.

Type: Historical Survey

Release: Curate LA

Reference: Checklist

Preliminaries: Catalogue of Previously Exhibited Works.

Publication: Digital Catalogue (Part 1, Part 2); Limited Edition Print Catalogue.

Press: Review by Joseph A. Hazani (A Dilettante: September 23, 2023); This Week’s Must-See Art (Curate LA: August 24-August 30, 2023); Film by EMSARTS (August 27, 2023).

Recordings: Exhibition Videos.

Events: Piano Performance (Release); Curator Walkthrough (Release).

….

Please contact Emily Reisig with any questions: gallery@reisigandtaylorcontemporary.com

The Limited Edition Print Catalogue for the exhibition is available here.

____

____

Reisig and Taylor Contemporary is honored to present Magaxat, a historical survey of paintings, prints, and sculptures by Rudik Ovsepyan (b. 1949: Leninakan, Armenia). The timeframe of the exhibition is 1976 – Present.

Ranging from the bucolic landscape sceneries that formalized his (former) career as a Soviet artist to his current material-focused, process-driven works in abstraction, the exhibition recovers autobiographical traces of Ovsepyan’s evolving practice across multiple languages and multiple countries he has called home. Displaying personally and historically significant works from each period of dwelling in a different place—Armenia (USSR), Germany, and the United States—this first historical survey of Ovsepyan’s work focuses on transitional phases of his oeuvre. The selected works demonstrate an anticipatory or consequential relation to the irruption of his singular mode of abstraction that emerged in the wake of the 1988 Spitak earthquake in Armenia. In particular, the exhibition will show transitional works from his Red series (1988-1992), produced directly in response to this traumatic event, as well as new and unseen works from his time in Germany and the United States. Ultimately, this driving work in abstraction (and refusal to paint propaganda) caused him to be banned as a Soviet artist, and motivated him to immigrate to Germany, and then the United States, in order to continue his insurgent practice.

The title of the exhibition, Magaxat, the artist’s transliteration of the Armenian “Մագաղաթ” (‘Magaghat’), or “parchment,” into Latin script, is taken from the name of one of the metamorphic series of painted/sculpted paper works included in the exhibition. Coupling irregular, tattered-seeming edges with the sinewy yawn of paper mummified in oil and wax, the artefactual materiality of the surfaces in this series remembers the leathery parchment scrolls of a medieval manuscript. Embedded within and strung across the rigor mortis of the material, illuminated patterns of symbols and letters are threaded into a grid and glyphically carved into the paper, suggesting the supple furls of a scroll and the eroded reliefs of a stone tablet through the same contradictory (but harmonious) form. Illegible, or nearly so, but demanding to be interpreted and read: the flesh of each Magaxat, of each “parchment,” forms a record of a body—a language, a technique, a trauma, and a transmigration. Encountered again and again, this formation of a record through materials and symbols, of holding the imprint of a body and its writ(h)ing, appears as a minimal activity of each work presented in the exhibition.

Deeply influenced by the intricately structured miniatures of Armenian illuminated manuscripts (as well as the ornate patterns of Armenian rugs), each of Ovsepyan’s works contains at least a single strand that strays back to traditional Armenian artforms. However, at the same time, and with equal force, Ovsepyan’s work springs from the attributes and corporeality—or the particular vulnerability—of the material itself. Among the (more recent (2000-)) mixed-media works from the Labyrinth, Zaun, and Magaxat series, the material process is focused on paper. In earlier works, such as the oil/tempera paintings of his landscape sceneries and his Red series, there is still an emphasis on material, but in terms of the locality of the oils and the autochthonous pigments used to produce the works. Followed as a progression, the survey demonstrates a gradual evolution from (1) either realistically, impressionistically, or expressionistically representational, studied paintings of places and people (including state works); to (2) process-driven works inspired by traditional Armenian artforms; to (3) the automatic, material and process-driven works derived from the qualities of the material and autobiographical relations between texts, objects, or structures. (4) In-between and within each of these phases, techniques borrowed from printmaking recur as interventions between the textual, imagistic, and material dimensions of the work. (The exhibited “Russian Still Lives,” produced in Germany (1998-1999), are exemplary culminations of his experiments with printmaking.) However, Ovsepyan’s oeuvre is, fundamentally, more cyclical than linear, and he repeatedly returns to prior modes of production through new or evolved attitudes or means.

Centrally positioned (between 2005-2006) along the timeline of the exhibition, and uniquely situating a metonymic reference to Armenian manuscripts (produced on parchment) while remaining directly uttered through the material itself (“parchment”), Magaxat names a constant tension between material and symbolic registers throughout Ovsepyan’s work. A material symbol, and a symbolic material. Holding this tension, the exhibition asks: is the work a message or an image (or both)? An artefact or an artifice? A sacred object or a worldly—even cursed—image? An incorporation or a figuration (or a signification)? A writing or a sculpting? Or, materially and theoretically, what is a record (of a body) and how is it formed? And, how does this record-keeping demonstrate or keep track of—and resist—patterns of territorial governance, political persecution, imperial distribution, (an)aesthetic regulation, and economic discipline of bodies? Collectively, the works begin to respond to these critical questions about power and the relations of identity, history, language, catastrophe, and exclusion through metropolitan structures of organization and displacement.

Although much of Ovsepyan’s life has been initially guided by histories of Armenian statelessness, personal displacements, and extrinsic politics of his artwork as a Soviet artist operating with a double practice (one of the state, one of his own), intrinsically, the political dimensions of his work are much more subtle and nuanced than a simple rejection of socialist realism or an insurrectionary strategy. In his words, “I only work.” Observably, it is precisely the abandonment of this double practice, when he begins to make only what he wants, and stops taking payments for political murals or propaganda paintings—and, rather, enters the market through his “true” artwork—that his work truly becomes political (as a radical, non-state and anti-market, form of work). In other words, his politicized art was not political, but, rather, dogmatic, representative, and simply fulfilling a professional duty (a form of labor). This is verified by the fact that it was his abstract work, not his explicitly politicized state work, that led to the political problems with his practice. Therefore, political stakes that emerge from his work are a consequence of the frictions the work itself finds with the surrounding world, and less an intended program of the artist. The politics of aesthetics, the resonances of his artforms, are already-there in the material of the works: their bodies threaten the orders they usurp. The work overtakes the labor. His artwork archives, threads, and molds—an activity of recording a body’s movements without the funneled commentary of a representation, a remark, or a revision. Ovsepyan’s practice is one of presentation, demonstration, and preservation of civilizations’ refuse and societies’ fragments, recovering and re-remembering the rejected, cast-out, and the set-adrift along the margins of the continually shifting limits of empire. He builds his view of a stateless metropolis through a hagiography of humanity’s faults, beginning with the ancient strains of Armenian material culture and carrying that history every place he passes-through.

Performing the subject of the painting or sculpture through material techniques and automatic processes, each work produces an artefact of Ovsepyan’s lifelong movement through filmic residues or membranes of (passing) time and (changing) place. This is evident across all of his work, and particularly in his paper works consisting of newspaper clippings, crossword puzzles, musical scores, recycled cardboard from his moving boxes, and litter collected in his neighborhood. Perhaps this assembling of interstitial items begins with Ovsepyan’s work as an antiques collector and restorer in Armenia (a business that was destroyed by the earthquake). It seems each found object included in his pieces finds a path through the people and places from which it falls away. The title, too, performs this bodily task of demonstrating a path through space, time, and language: peculiarly spelled and unreadable for most, written between languages in the wor(l)d the artist has made by the contours of his displacements. A word—a record—that familiarizes whatever it states in the signing of its estrangement, handing-over the sheer materiality of the letters. Like the edges of a labyrinth that only occur to record (or dis/orient) the movements of a body, the exhibition realizes the recurring constellations of letters, lines, borders, topographies, and lacunas of Ovsepyan’s oeuvre as a collective composition of a body rendered through its dislocations.

….

Born in 1949 in Leninakan, Armenia, Rudik Ovsepyan became a member of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (CCCP) in 1982, eventually being banned for his refusal to paint in the propagandistic style of “social(ist) realism” (while continuing to produce and show abstract works). From 1966-1969, he attended Terlemesyan Fine Art College in Armenia. In 1974, graduated from the prestigious State Academy of Theatre and Fine Arts in Yerevan. Facing the widespread destruction of the 1988 Spitak earthquake, as well the evolving political turmoil surrounding his abstract painting, Ovsepyan and his family moved (by boat) to Germany in 1990, where he became a member of the Fine Art Association of Germany (in 1994). There, several solo and group presentations of his work occurred in gallery, state, fair, and museum exhibitions. In 2000, a major exhibition of Ovsepyan’s abstract works with oil and paper produced between 1996-1999 was presented by the German ministry of Education, Science, Research and Culture of Schleswig-Holstein (presented in Kiel). Later that year, Ovsepyan immigrated to the United States and began working on new bodies of work, including Labyrinth, Magaxat, and Zaun, while also beginning to produce mixed-media sculptures. A selection of his works was exhibited with Reisig and Taylor Contemporary at Art Market San Francisco in April 2023.

Ovsepyan’s works are included in public and private collections in Russia, Europe, Israel, Canada, and the United States, including: UNESCO, Geneva, Switzerland; Pushkin Museum, Moscow; Museum of Modern Art, Armenia, Yerevan; Museum of Modern Art, Georgia, Tblisi; Sparkasse Schleswig-Holstein, Germany; Sparkasse, Muenster, Germany; Provinzial Versicherung; Bundesministerium der Verteidigung, Kiel, Germany.

_____